Founded as a blog in 2008 by Charles “Chuck” Marohn, a land use planner and civil engineer, Strong Towns has since developed into a non-profit media advocacy organization with a fulltime staff and thousands of members. The organization posts media content, including articles and podcasts, and provides a growing variety of educational services on topics related to land use, transportation, and urban planning, housing and community development, and municipal infrastructure and finance.

The organization and its ideas are frequently linked to an appreciation for the way in which communities were developed and the physical characteristics of places built prior to the mid-20th century. As indicated by the coordination of Strong Towns first national gathering in May 2023, the organization is also associated with the New Urbanism movement. Central to the Strong Towns message is both a critique of what proponents refer to as the suburban experiment and veneration of traditional patterns of development.

The Suburban Experiment

The suburban experiment is often characterized by institutional finance, chain businesses, single-use and frozen-in-time zoning, low-densities, and other aspects of sprawling real estate developments oriented around cars. For the Strong Towns organization, the landscape of shopping malls, office parks, government centers, recreation areas, and McMansion subdivisions assembled along a dendritic and hierarchical roadway system produces fragile places. Not only does this development pattern, which was widely disseminated across the American countryside in the decades following the Second World War, induce traffic congestion and danger, degrade the environment, and create an aesthetic dessert, the suburban experiment also fails to produce long-term wealth.

The vast infrastructure of stroads, piped water, sewers and stormwater drains, electric and cable wires, and piped gas needed to support the suburban experiment create liabilities for municipalities that require routine maintenance, replacement, and upgrades throughout their lifecycle. The short-term prosperity of development fees and tax revenue are often dwarfed by these ongoing and longer-term infrastructure liabilities. One of the results of this pattern of development can be insolvent municipal finances, but Strong Towns has made clear the many problems with the suburban experiment.

Compact Development

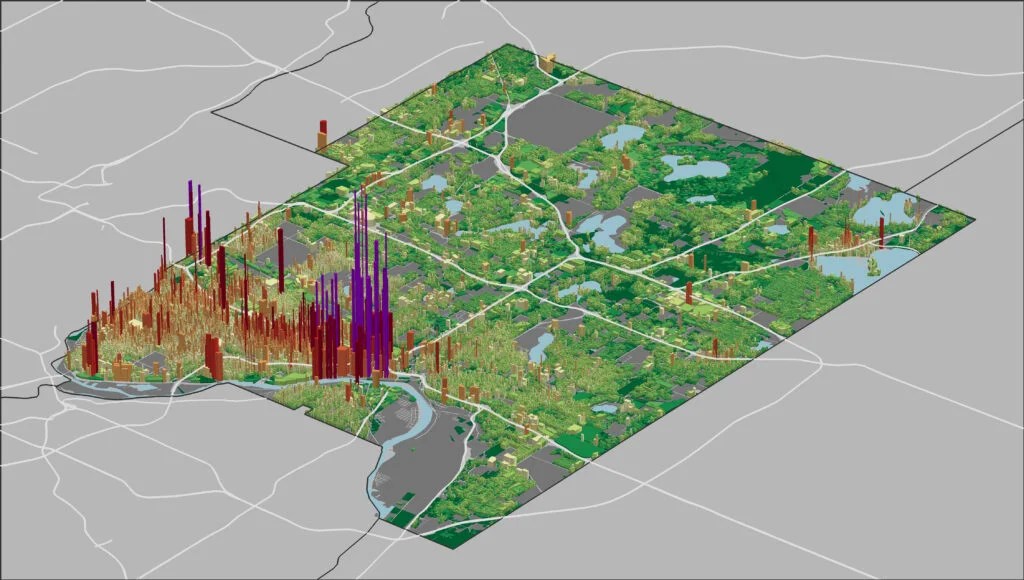

The Strong Towns message is not limited to critiquing the built environment. The organization has also developed a coherent set of guiding principles and specific examples for addressing the financial, aesthetic, cultural, and other critiques of the suburban experiment. To help inform their perspective, Strong Towns draws from a variety of sources on contemporary urban theory and practice. One such example is Urban3’s land value per acre analysis, which Strong Towns has incorporated and promoted in their work.

In essence, Urban3’s analysis shows that mixed-use, higher-density, and compact development generates far more tax revenue than the sprawling single-use residential and commercial areas characteristic of the suburban experiment. Equipped with this analysis, Strong Towns advocates for land use and development regulations that foster the creation of compact and mixed-use communities. Mixed-use and multi-story buildings organized around a distributive grid of narrow streets and served by transit are better equipped to support long-term maintenance of infrastructure. In many ways, this denser and more transit-oriented development pattern creates strong and anti-fragile places.

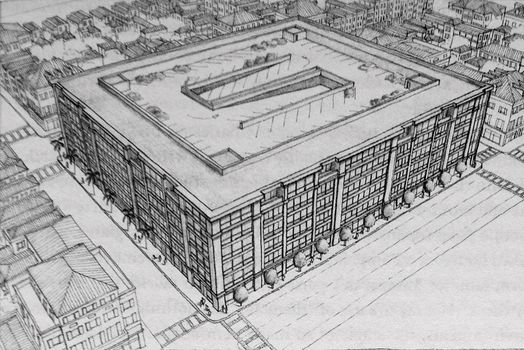

Without a doubt, compact, transit-oriented, and mixed-use development out performs sprawling, car-oriented, and single-use development in a number of metrics, including tax revenue and infrastructure finance. Through Sprawl Repair, it’s even possible to transform underperforming suburban areas into higher-performing mixed-use centers. Still, this transit-oriented development pattern is not entirely safe from the Strong Towns critique.

From the Strong Towns perspective, many mixed-use and multi-story developments share certain disadvantages with single-use and lower-density developments despite the surface-level differences in appearance. While compact development can achieve a level of walkability and urbanity that shopping plazas, office parks, and tract housing often lack, both share the characteristic of being large-scale and coarser grain development patterns. The presence or absence of sidewalks, street trees, and storefronts with apartments above belies similarities in how McMain Streets and McMansions are planned, financed, constructed, and managed.

Large-scale developments, whether more urban or more suburban in appearance, require well-capitalized developers, tens or hundreds of millions in financing from big banks and institutional investors, well-insured Architectural, Engineering, and Construction firms, and other real estate professionals that are unlikely to be sourced from within the local community where development is occurring. Commercial tenants of large-scale developments are more likely to be chain retailers interested in signing 10-year triple net leases. And unfortunately, money spent in chain stores is far more likely to be exported out of the community than money spent in locally-owned businesses. As a result, most of the expenditures, revenue, and value of large-scale developments is extracted out of rather than distributed within the places where they are built. The money needed to finance large-scale development can be – to use Jane Jacob’s term – “cataclysmic”.

Small-Scale Development

To address this critique of large-scale development with urbanistic appearances, Strong Towns draws from a wealth of smaller-scale and more bottom-up approaches to planning and development. While many of the goals of large- and small-scale urban development, such as walkability, transit-orientation, diversity, and beauty, may be shared, the two development processes differ in important ways. One difference is that large-scale development often extracts wealth, whereas small-scale development naturally lends itself to generate wealth within the community. Large-scale development requires complex financing and qualified professionals to deliver a successful project. It is unlikely that the local real estate broker, credit union, and tradespeople in your community will be able to undertake the development of several-hundred units of housing all at once. There is nothing inherently nefarious about this – it’s just the inevitable result of completing a large project is a short amount of time, which requires the use institutional finance.

Encouraging large-scale dense development can be an effective strategy for maximizing local property tax revenue for the municipal government. It is not, however, a particularly effective way of maximizing the distribution of real estate expenditures, revenue, and value within the community. To address this, some communities have looked to exact development impact fees, local hiring requirements, unionization of support staff, and other measures on large-scale development projects in order to better ensure that wealth generated from real estate development benefits the local community. Another approach, and the one championed by Strong Towns, is to encourage smaller-scale and finer grain development. While small-scale projects do not require the use of local finance and professional services, small-scale development can be, and often is, undertaken by local real estate brokers, lenders, and tradespeople without incentives or requirements from government.

For Strong Towns, places that maximize the distribution of community wealth through widespread small-scale development are stronger and more anti-fragile than places that maximize the concentration of taxable real estate value through pockets of large-scale development. To this end, Strong Towns has promoted the work of organizations like the Incremental Development Alliance, which trains local residents to become small-scale developers and business owners. When unleashed through incremental upzoning and other Lean Urbanism land use and development regulatory reforms, this swarm of small-scale developers can create increasingly mixed-use, fine-grained, dense, and complex places oriented around walking and micromobility. These places will be populated with ADUs, ‘plex houses, townhouses, courtyard apartments, mixed-use walk-ups, and other missing middle development types.

Conclusion

Strong Towns has effectively drawn from a myriad of sources to inform its work. The organization has convincingly argued that places populated with dense mixed-use buildings served by transit are stronger economically, aesthetically, and socially than places created under the suburban experiment. The distinction Strong Towns draws between large- and small-scale development further develops the idea that places built by many hands over time are stronger than places built instantly by a few hands. These are key insights.

However, as convincing and powerful as the Strong Towns organization’s arguments often are, there is a central question, at least for me, lingering underneath the surface. If some places are stronger than others and places are capable of becoming stronger, then what characterizes the strongest and most anti-fragile places? Does there need to be an ideal towards which to strive? What is that ideal? What is the Strong Towns telos?

Strong Towns proponents might respond by saying that encouraging smaller-scale and more finer grain development will make a place stronger than larger-scale and more coarser grain development. Gradually developing to the next increment of land use intensity is better than rapid change in development intensity and scale. Placing decision-making authority in the smallest and most local body of government through subsidiarity makes more sense than giving distant bureaucrats control over local and hyperlocal matters. How can the accuracy of these claims be measured? Through what means and metrics?

Can the strongest and most anti-fragile place best be described by its physical appearance and attributes? Can it be described by people’s spatial and sensory experiences of the urban form of a place? Are increases in land use density and intensity necessarily an indicator of strength? Must strong places change over time? How is stability distinguished from stagnation? Is the strongest, most ideal town measurable by a chart of municipal revenues and expenses? Or by the collective wealth of the community? Is the strength of a place ultimately dependent upon its inhabitants, their beliefs, and their actions?

If a place’s inhabitants are individually animated towards communal action by a set of beliefs, convictions, and narratives, then will it naturally and inevitably follow that the physical appearance of the place will be aesthetically pleasing, the municipal budget will be balanced, and wealth will be widely distributed? If so, the question then becomes: what is a set of beliefs that can animate people into developing a culture of building the strongest places and strengthening existing ones?

I’m curious to hear the Strong Towns response to that question. For my answer, check out existing content and be on the lookout for future content from DEMOCRATIZE DEVELOPMENT.

2 thoughts on “Strengthening Places: A Look At The Strong Towns Organization”