In September 2023, Current Affairs, an online magazine with a politically-left perspective, published The Strong Towns Movement is Simply Right-Libertarianism Dressed in Progressive Garb. The article, written by Allison Lirish Dean of Progressive City, offers a critique of Strong Towns, a non-profit media advocacy organization. Democratize Development has previously written about Strong Towns here. Throughout the Current Affairs piece, Dean presents her [mostly fair] understanding of the Strong Towns’ position on several urban planning topics followed by her critiques. As the following post will explore, the author’s arguments include constructive criticism, differences of opinion from (rather than refutations of) Strong Towns, as well as some misunderstandings of urban history and theory.

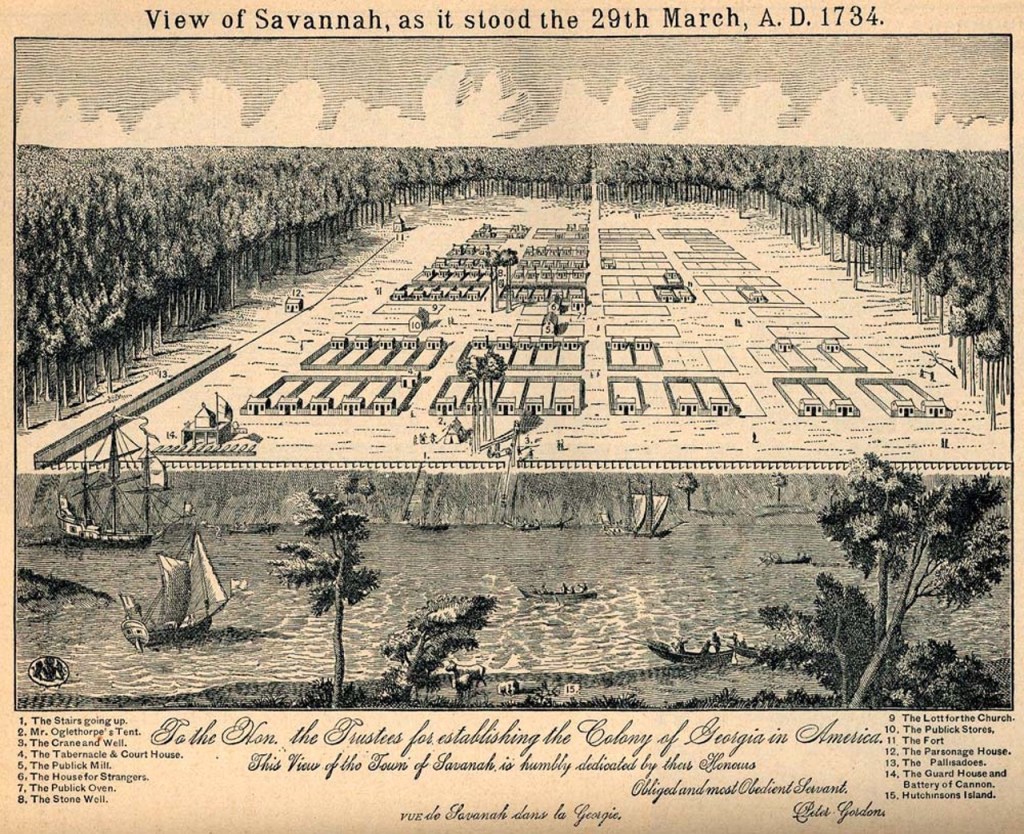

In the Current Affairs article, Dean discusses her understanding of Strong Towns’ perspective on urban planning, which is informed by her digestion of Strong Towns’ media and interviews with leadership, including the movement’s founder Chuck Marohn. The author finds several of Strong Towns’ points on various topics compelling and in alignment with her sensibilities. However, contentions quickly arise in the article. One such contentious topic is whether or not the historic development of Savannah is an appropriate example of Strong Towns’ philosophy in action.

the Public Sector’s Role in Planning and Development

Dean portrays Marohn and his Strong Towns Movement as broadly anti-government whereas, according to at least one scholar, the public sector at the local level played a central role in guiding Savannah’s early development. Surely then Savannah cannot embody the Strong Towns agenda. Except that I very much doubt Marohn would describe himself as anti-government or deny that government has an important role to play in planning and development. My sense is that Strong Towns is trying to rediscover and distill many of the planning and development principles that gave rise to the kind of urbanism found in places like Savannah.

Strong Towns argues in favor of a role for the public sector that is appropriately balanced with other sectors so as to initiate and sustain processes of urbanization as exemplified by many (not all) aspects of pre-World War II Savannah. This is not an anti-government sentiment. The public sector at the local, regional, state, and federal levels needs to be appropriately-scaled, -funded, and -tasked so as to be in balance and harmony with other sectors. If the public sector is too small and limited, things like substandard housing conditions among working class renters may proliferate. Likewise, government that is too centralized or expansive, may stifle private sector housing development with onerous regulations and taxation, thereby restricting housing supply and reducing options for working class renters.

Further digestion of Strong Towns media and discussions with leadership may reveal to Dean that any disagreement about what Savannah’s development history exemplifies is more semantic than substantive.

The Issue Facing Public Transit

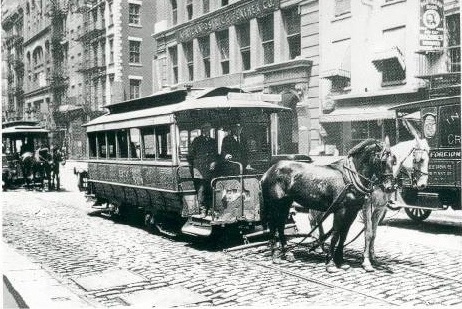

A major point of contention arises in the Current Affairs article around the issue of how to finance and operate transit service. To discuss this issue, some historical information is helpful.

Many cities’ early transit services were initiated as private business ventures. In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, cities were home to a growing population of people with disposable incomes who were both able to afford to pay a modest fee for transportation to and from residential, employment, commercial, and leisure destinations, and also willing to pay such a fee in exchange for that service. Groups of entrepreneurs became aware of this. In response, they developed business plans for horse-drawn streetcars traveling on railroads within the public right-of-way and along routes for which entrepreneurs suspected people would want to ride and be willing and able to pay.

These groups of entrepreneurs would then seek out financiers and the rights the build railroads within the public right-of-way. The financiers, sometimes land speculators, would provide the capital, in the form of debt or equity in the business, to build the infrastructure and begin operations of transit service along a corridor. Overtime the fares collected from passengers would be used to pay for operating expenses, repairs and upgrades (like to overhead electric wires), and to pay down the debt from the initial and ongoing investments.

If the entrepreneurs made bad assumptions about the location or future ridership of their transit line, they may not have been able to collect sufficient fares to cover costs and the business might go bankrupt, close down, and have to sell off assets to pay off debt, and the investors could lose their money. Successful streetcar lines, meanwhile, might be expanded, the number of cars operating on the line might be increased, and the land along the route might become more valuable and get developed more intensely. Really successful transit businesses might start buying out the other streetcar lines from their owners and consolidating and streamlining operations to achieve economies of scale.

As Dean mentions in her article, the proliferation of personal automobile ownership in the first half of the twentieth century severely impacted the ridership and operations of fixed path transit like streetcars and buses. Traffic-congested urban streets reduced transit travel speeds, increased frequency of stops, and made using transit less desirable and convenient. Middle class riders often moved out to new sprawling suburbs with residential, commercial, industrial, and recreational enclaves built around trucking and automotive commuting. Declining overall ridership, decreasing middle class ridership, less efficient service, and spread out service areas and destinations resulted in fares no longer covering operating expenses. In the second half of the twentieth century, many private transit companies went bankrupt and were acquired by local, regional, or state government agencies.

Today, most public transit agencies seek to provide service to people who want it regardless of riders’ ability to pay for the operating costs of that service through fares. The government adopting the failed business model of unsuccessful private transit operators that went bankrupt and lost their investors’ money as a strategy for providing public transit service has not worked out well for the tax payer investors. So is the primary issue facing transit, as Dean contends, a lack of will to impose transit costs on communities regardless of their interest in or ability to fund those costs through taxation? Or is the primary issue a lack of the urban conditions that are required to make the provision of transit service possible and allow viable transit service providers to emerge?

Perhaps there is an opportunity for a movement that advocates for fostering those urban conditions that support transit in our sprawling contemporary built environment. Maybe an organization that advances arguments for redesigning stroads, redeveloping single-use enclaves, intensifying land use in existing low-density neighborhood, and strengthening towns will emerge someday.

The Value of Heterodoxy

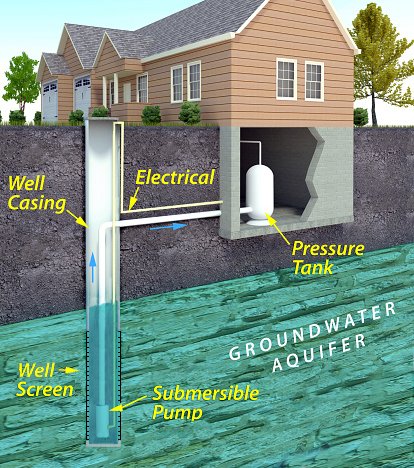

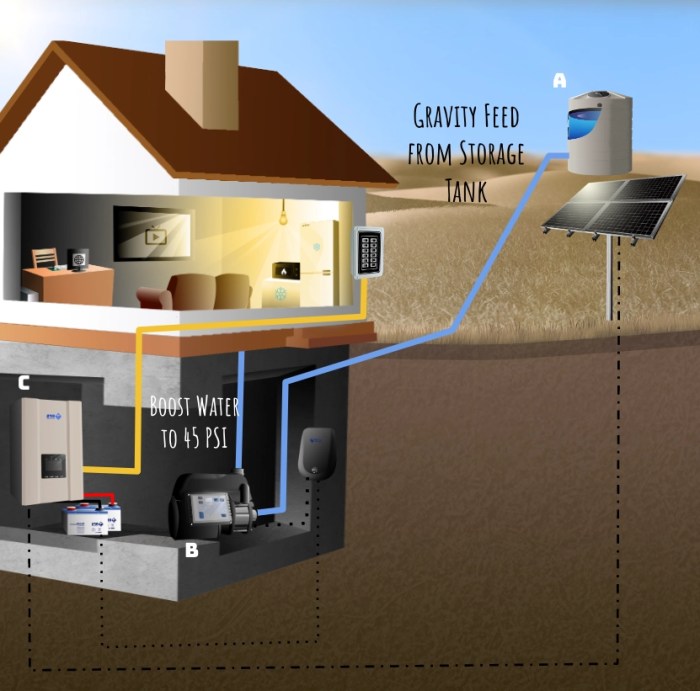

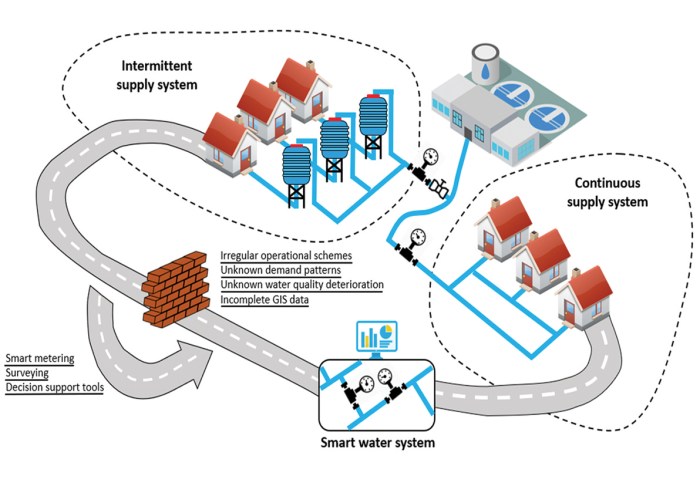

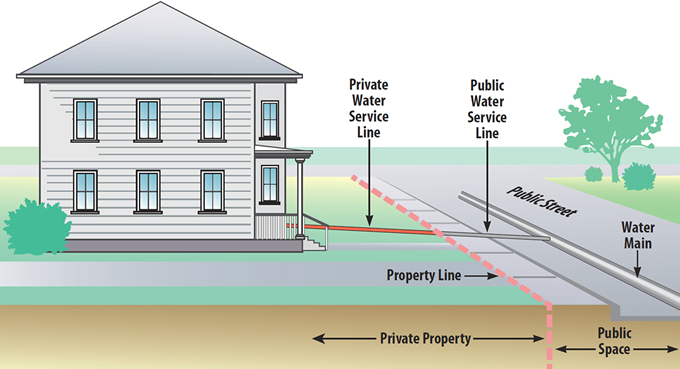

Dean’s next criticism revolves around Marohn’s suggestion that there are a variety of ways to think about supplying water for fighting fires, showering, watering lawns, toilets, and drinking. In the context of Flint, Michigan, which has faced issues related to drinking water contamination, Marohn wonders if a single centralized piped water system serving all those uses is the best and only option. Dean is convinced that separate water services for different uses is neither practical nor ethical for a community like Flint. She may be right about the practicality of such a proposal, but there is value in Marohn’s way of thinking about an issue like the supply of water to cities.

Too often people take our modern urban systems for granted without appreciating or understanding how they emerged, what sustains them, and what alternatives are available. Strong Towns has contributed important insight into the history and development of piped water and gas, sewer and stormwater drainage, electric and telecommunications service, and other urban systems that our cities depend upon. Understanding how different utility services and infrastructure systems were created and what options exist for delivering them today is helpful in decision-making around maintenance, expansion, and improvement of these systems.

There are advantages and disadvantages to supplying water via home water tanks filled up by water trucks versus separate piped systems for different uses versus one centralized network. One is not right and the other wrong. One may be better in a given situation than another, but there are trade-offs between cost, reliability, control, and risk no matter which system is chosen. For instance, paved streets and sewer infrastructure were installed in inner city “slum” and fringe suburban neighborhoods in the early twentieth century in accordance with public health policies. It has been argued that this contributed towards many more people losing their homes through foreclosures during the Great Depression than would have been the case if the installation of that infrastructure had been delayed or built more incrementally. Basic provisions like potable water, shelter, and food being available to everyone regardless of their income is a good goal. Failing to match the methods of making basic provisions available to a community with that community’s ability to pay for the method is bad policy. Imposing expensive services and infrastructure upon communities regardless of their ability to afford it is not ethical.

Limitations of the Private Market

One of Strong Towns’ central calls is to unleash small-scale private developers in neighborhoods to do the work of building ADUs, plexes, cottage courts, mixed-use walk-up buildings, and other missing middle-style buildings. If empowered to do so through various regulatory and financing reforms and training, Strong Towns claims that these small builders will be able to create a wide variety of housing that improves overall affordability in the housing market, local wealth creation, and fiscal stability, among many other socioeconomic benefits.

According to a 2020 study, landlords who own just a few rental units tend to live closer to their tenants and file fewer evictions as compared to landlords with large portfolios. Anecdotal evidence also supports the idea that mom and pop landlords tend to charge lower rents than large-scale institutional real estate investors who are more likely to use formulas and property management services to maximize rent. Smaller-scale development also lends itself to local sourcing of finance, building materials, and labor to a greater extent than large-scale development, which often requires highly-capitalized investors and well-insured architectural, engineering, contracting, and law firms.

There are benefits that small-scale builders and development offer to communities, but, as Dean correctly points out in the Currant Affairs article, there are also significant limitations to what private developers, no matter how small, can do to build community. One of these limitations is in providing housing that is affordable to low-income households. As Cameron Murray convincingly argues, the private market can typically only provide housing to the poor through slums, or substandard housing.

Community Planning and Development

In her article, Dean imagines that advocacy around issues like increasing wages and reducing workday length will result in more people participating in community planning efforts. I doubt Strong Towns would object to that. The distinction between what Strong Towns is interested in and what Dean presents as the Progressive position is in what the two foresee resulting from community planning processes.

Often times community planning meetings consist of a couple scenarios. In the first scenario, local public officials will solicit input from members of the public to envision the future of their community. In the second, a developer is seeking a public concession in the form of zoning relief or subsidies and community members are given an opportunity to weigh in. Dean and Marohn would both likely recognize these scenarios and have concerns about them. Participants in community meetings tend to consist of older and wealthier homeowners in a community who have free time available to them. Many of the comments expressed by this group of Neighborhood Defenders can range from unrealistic expectations and infeasible goals for their community’s future to irrational fears about development on the one hand and legitimate grievances about the lack of opportunity to influence projects that have already been finalized behind-closed-doors on the other hand.

Strong Towns envisions a different community process whereby meeting attendees are transformed from passive observers and commentators on development proposed in their community into active participants in their own development of their community. This requires providing residents with information and training on demographic trends, market opportunities, real estate finance, and managing small-scale development projects. Dean might see the private sector’s limitations in such a proposal even if the developers are members of the community. I get the sense that Dean’s ideal community planning process would instead steer participants into advocating for greater public sector participation in housing and urban development through governmental entities.

There is an opportunity here to clarify and expand our terminology around these topics that I believe will benefit both the Strong Towns and Progressive planning movements. Strong Towns also often deploys a metaphor that compares bees swarming to small-scale developers. I’ve previously written about my concern with how Strong Towns uses this metaphor here. There is also a problem with limiting discussions of housing and real estate development to what the private and public sectors can do. There is a third sector that is important to consider.

Private, Public, and Popular Sectors

Dean misinterprets Strong Towns when she assumes that small-scale development would solely produce housing for the private marketplace. To be fair, Strong Towns does not clearly differentiate private and popular sector development. In the Current Affairs article, Dean calls for renewed investment in Public Housing as a preferred method for housing people who are unable to afford housing in the private marketplace. Identifying the differences between the private, public, and popular sectors would assist both Strong Towns and Dean.

Examples of private sector development include a large-scale suburban shopping center or mixed-use building, or a small-scale missing middle-style project that is developed by a private developer. An example of a public sector development would be a traditional Public Housing community that is developed by a government agency. A popular sector development could be a person improving their own home or organizing to buy a multifamily apartment building with their fellow residents. In other words, a popular sector development is developed by the end user for their own personal use rather than for sale, rent, or use by another person through a marketplace (though the line between popular and private can become blurred if a homeowner builds an ADU, for instance).

When Strong Towns advocates for small-scale development, they sometimes mean small-scale private development and other times they mean small-scale popular development, though they have lacked the terminology to make such a distinction until now. Just as there are significant limitations to providing affordable housing in private markets, the capacity for government to participate in housing – whether by subsidizing the private market or building Public Housing – is also limited. There are important differences in the abilities of the private, public, and popular sectors to meet housing demands of low-income households. On a level playing field, the private and public sectors are much more limited than the popular sector.

The Progressive Error

The Progressive tendency, as advanced by Allison Lirish Dean in her Current Affairs article, is to address problems through centralized, authoritarian public sector interventions by government “empowered to properly tax, redistribute wealth, and deliver broadly beneficial programs.” The Strong Towns approach is much more about promoting strategies that naturally distribute wealth broadly throughout communities without the need for a central authority to tax wealth and then redistribute it. Centralized collection of wealth through taxation more often results in incompetent, inefficient, and sometimes corrupt bureaucracy than it does efficient and effective redistribution. Belief in strong centralized governments can often lead to diffusion of urban responsibility, wherein residents can come to believe that the provision, management, and maintenance of systems like piped water and gas, sewer and stormwater drains, street trees, and other infrastructure is the responsibility of some abstract governmental body or agency rather than their own. Strong Towns empowers individuals to take responsibility for the urban systems they use. A society consisting of individuals in the former group will not be able to sustain or maintain complicated urban infrastructure. A society consisting of the latter group of individuals will be far better equipped to setup and maintain processes for managing infrastructure.

Let’s take the issue of nutrition as an example. It can be observed that acquiring nutritious food is often more expensive and less convenience than junk food. This can be particularly true for lower-income households living in lower-resource and -opportunity communities. Should the Progressive solution focus on creating government agencies to build tax-exempt non-profit full-service restaurants that subsidize the costs of meals for households that can’t afford to eat at a private restaurant for every meal?

As I understand it, the Strong Towns approach would take a different perspective. Strong Towns might encourage local residents to grow herbs in window boxes and plant vegetable gardens at home, work with neighbors to create a community garden, start a community kitchen and farmer’s market, allow homeowners to build corner stores, cafes, and restaurants as Accessory Commercial Units, incrementally upzone neighborhoods to create the residential density needed to support a grocery store, and a range of other community development initiatives that provide a variety of food options to people. Any gaps in food access that might remain could be addressed through some form of publicly-funded supplemental nutrition assistance program.

With housing, should creating tax-exempt non-profit Public Housing be the focus of Progressive efforts to address housing affordability crises? Is the best way to measure housing affordability by analyzing median household income, costs of new housing construction, and median home prices? Isn’t that akin to measuring nutrition affordability by analyzing median household income, costs of meals prepared in restaurants, and median meal price? Can Progressives also put their energy into advancing a wide range of bottom-up community development initiatives that result in residents building their communities with lots of different housing options and strategies? Any gaps that may remain can be closed with some form of publicly-subsidized supplemental housing assistance program. In the rare situations where people are incapable of housing themselves through private and popular sector strategies, Public Housing may be necessary, but private and popular sector development initiatives should suffice for the vast majority of people.

Progressive City is simply authoritarianism dressed in democratic garb. Strong Towns is seeking to balance private, public, and popular sector development under a philosophy of subsidiarity.

One thought on “Progressive City is simply Authoritarianism Dressed in Democratic Garb”