Escaping the Housing Trap, published in the Spring of 2024, is a book co-authored by Charles Marohn and Daniel Herriges that explores the contemporary American housing market from the perspective of the Strong Towns movement. In previous posts, I have reviewed Unleash the Swarm (another of Daniel’s books), discussed the Strong Towns movement, and analyzed criticism of the movement. Having been familiar with the Strong Towns movement since its early days as Marohn’s blog, I can comfortably say that I find the movement’s approach to issues related to transportation planning, urban development, and housing to be compelling. My view on Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis is no different.

I highly recommend this book to affordability advocates, public officials, planners, and anyone else interested in housing. The book provides helpful commentary on the private housing and real estate development market, the limitations of public subsidies to address affordability, and actions that ordinary people can take to begin addressing the housing crisis. Rather than summarizing the book or listing the many points of agreement, the following blog post will focus on a few inaccuracies, moments of disagreement, and other areas of the book that I think could be improved.

THE ORIGINS OF THE SUBURBAN MODEL OF PLANNED DEVELOPMENT

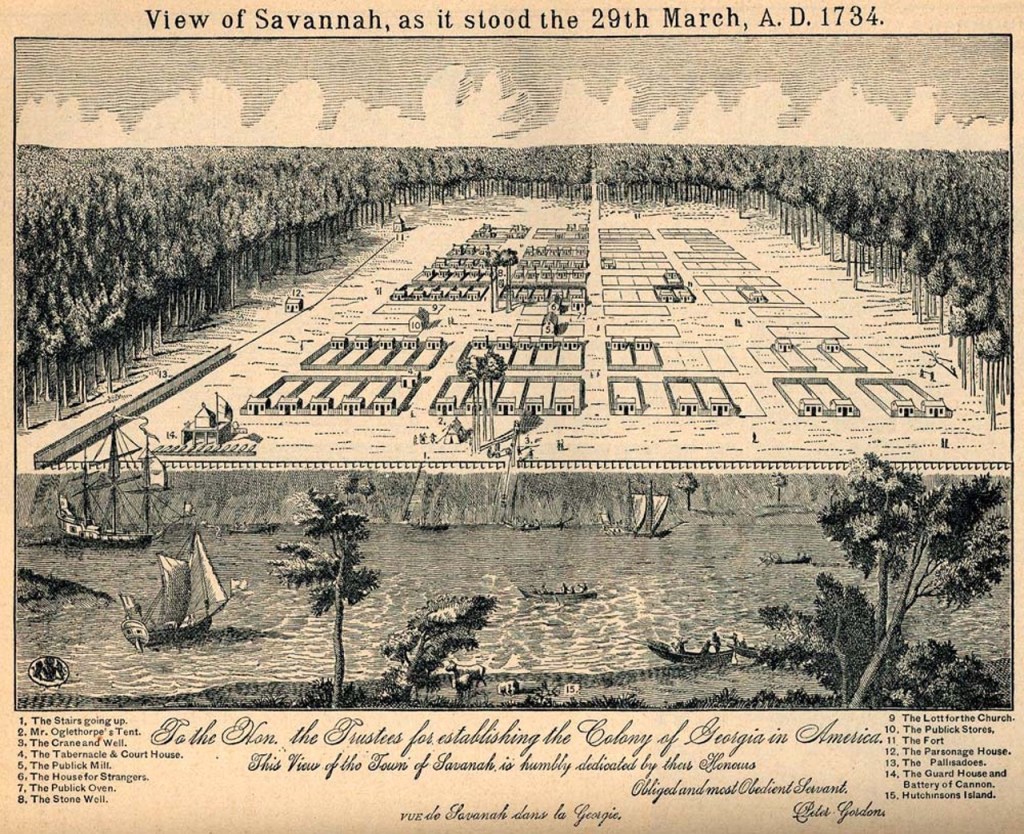

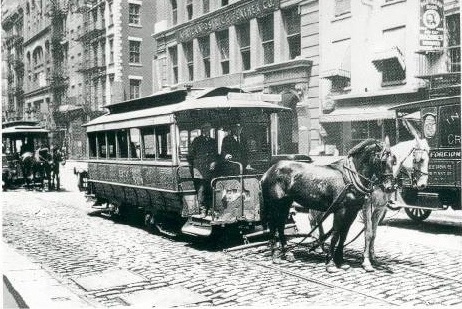

In Escaping the Housing Trap, Marohn and Herriges state that the pre-Great Depression housing crisis was largely one of quality. The authors go on to explain that through the New Deal the federal government got involved in private housing by insuring mortgage-backed loans that met certain criteria. This, it is argued, led to a way of developing housing that depended on debt and eventually gave rise to the suburban model of instant housing development. This is partially correct.

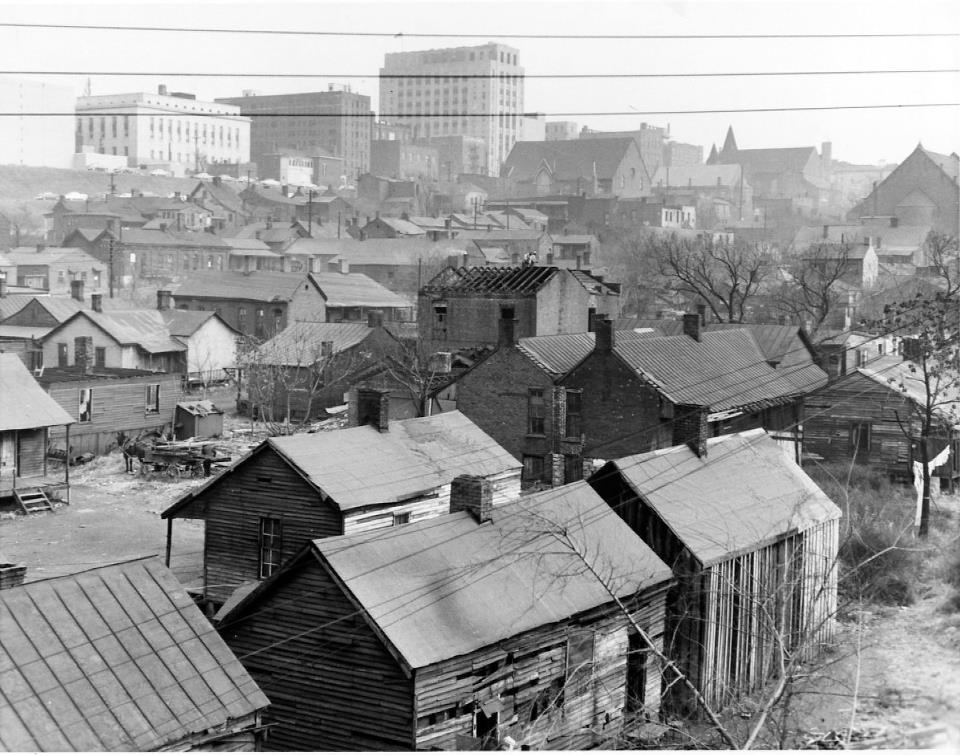

Prior to World War One, much of the housing available to the poor was indeed of very low quality as compared to what was available to households with higher incomes. Beginning in the late-nineteenth century and continuing into the twentieth century, municipalities adopted increasingly higher minimum standards for development in order to improve the health, safety, and quality of housing. By the 1920s, many local governments had adopted one or more regulations that greatly increased the cost of building housing. This, in tandem with other social and economic factors, effectively ceased the construction of new housing that was attainable to the poor. Instead, homebuilders focused on providing housing for the middle and upper classes and the poor increasingly had to rely on down filtering of existing housing.

“In finance, we had a pre-Depression status quo in which debt was not easily available as a means of securing housing.” p. xv

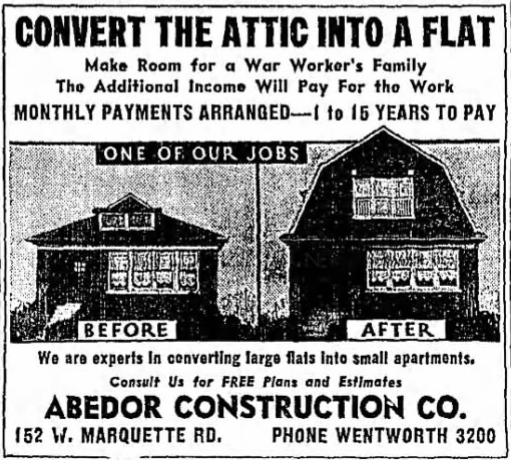

Even prior to the availability of federal insurance for modern longer-term lower-interest mortgage-backed home loans, debt- and special assessment-fueled housing and community development projects in the 1920s contributed towards the severity of the Great Depression. Reliance on debt-financed and instantly-developed urban and suburban housing predates the creation of the modern home mortgage. After the Great Depression, the federal government expanded its role in providing public housing and started getting involved in the private housing market. Federal insurance for mortgage-backed home loans helped mitigate the risks associated with relying on debt to finance housing development. And Federal insurance for home improvement loans (along with public housing) helped reduce the poor’s dependence on down filtering. In the 1960s and 70s, municipalities increasingly adopted restrictive land use regulations like zoning and wetlands ordinances, which essentially made highly planned middle class developments the minimum standard for constructing new housing.

JC Nichols, who was a key player in developing the model of instant development of planned suburban subdivisions, is discussed in Escaping the Housing Trap. And Herriges has previously written about the earliest roots of the suburban experiment. But the book’s presentation of the sequencing of events around the Great Depression and the authors’ understandings of the New Deal’s housing programs could use some refinement.

THE THEORY OF NEIGHBORHOOD SUCCESSION

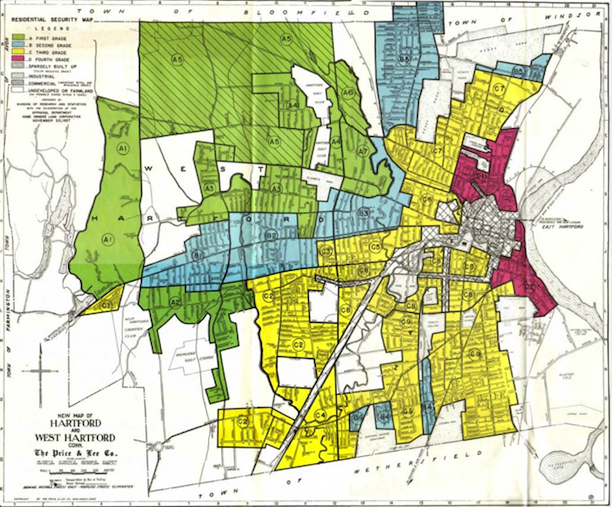

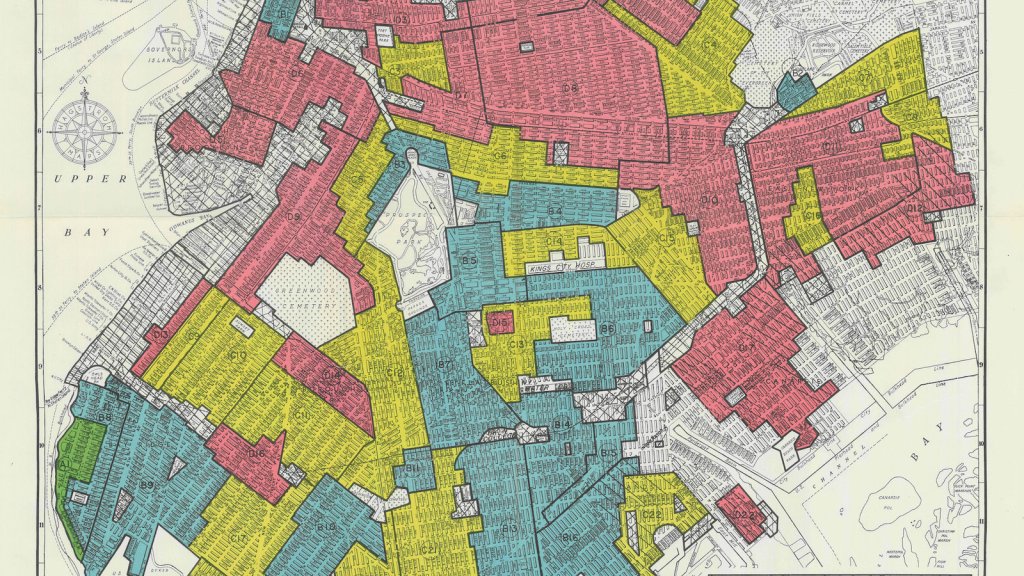

Many of the realtors, administrators, public officials, and other influential people who guided mid-century housing programs and policies subscribed to the idea that housing, like consumer goods, depreciates in value and that neighborhoods decline both physically and in desirability over time. These ideas are evident in the program guidelines, neighborhood maps, and other official documents that local realtors and bureaucrats produced for the federal government in the mid-twentieth century. It seems that Marohn and Herriges may subscribe to these beliefs as well.

“What happens to a neighborhood where permanence is the foundational understanding of its existence? Neighborhoods built all at once, to a finished state, experience an echo of maintenance. [A] neighborhood predicated on permanence will have a period – perhaps a couple of decades – where everything is shiny and new. After this, everywhere and all at once, decline will start to set in.” p. 40

How do the authors see a place like Levittown, New York, which was originally developed as a suburban subdivision development for a middle class community but has seemingly kept up with maintenance and retained, and even increased, its desirability over time? After a half century of existence, should we expect the streets, parks, and houses of Levittown to be crumbling? Since they aren’t, are we to assume that the community must be propped up by an unsustainable level of debt? Does Levittown possess some special physical characteristics that differentiate it from other declining suburbs? Is it an anomaly? Or are there larger economic and social factors at play in determining the fate of neighborhoods over time?

HOLC, FHA, AND REDLINING

According to Escaping the Housing Trap the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which was created under the New Deal to refinance home loans that were at risk of default during the Great Depression, created Residential Security Maps to guide its work. The authors also state that both HOLC and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) engaged in redlining by excluding urban neighborhoods and ethnic minorities from their programs.

“Neighborhoods that were coded red were considered the riskiest and were generally excluded from HOLC lending programs.” p. 23

HOLC actually created its maps after it had finished its work of refinancing millions of home loans across the country. The Residential Security Maps were made retrospectively. In fact, HOLC refinanced many home loans in neighborhoods that were subsequently color-coded red on its maps. Contrary to popular notions, HOLC’s refinancing program benefited large numbers of nonwhite homeowners and reviews of its lending practices have yielded no indication of discrimination on the basis of race.

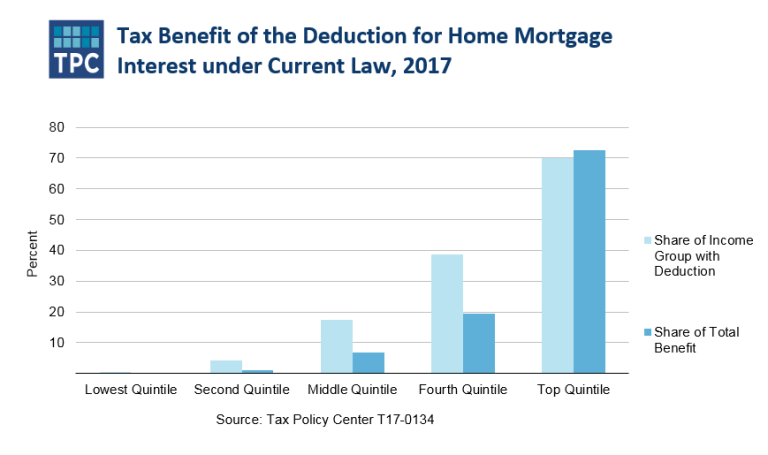

“The primary mechanism the FHA used was mortgage insurance.” p. 24

The FHA administered multiple programs, including insurance for mortgage-backed loans and for home improvement loans. Between 1934 and 1940, FHA insured more than four times as many home improvement loans as mortgage-backed home loans. Its true that FHA’s guidelines did discourage use of insurance for mortgage-backed loans in some urban neighborhoods. However, many of the mortgage-backed loans insured early on by the FHA in the 1940s and 50s in inner ring suburban neighborhoods would, within a decade or two, become home to ethnic minorities who were moving out of older city neighborhoods and replacing other families who were moving to newer neighborhoods.

There are also examples of the FHA insuring mortgage-backed home loans for nonwhite homebuyers in new subdivisions. It seems that the FHA may have primarily been skeptical of insuring mortgage-backed loans in aging neighborhoods that were undergoing change and whose stability over the term of an FHA-insured mortgage-backed loan appeared uncertain in the eyes of mid-century realtors. In 1968, the FHA revised its guidelines and began a concerted effort to insure mortgage-backed loans in circumstances that would not have qualified under previous guidelines. Within just a few years of beginning this effort, many urban homeowners defaulted on their loans and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development was left holding these properties. For some, this gave credence to the FHA’s prior concerns.

Even though FHA-insured mortgage-backed loans may have been difficult to attain for some people and in some neighborhoods prior to 1968, other types of loans were available. In addition to home improvement loans, rehabilitation loans became available in 1954 for financing significant improvements to substandard housing. Redlining aside, it is important to consider the market forces that had a significant impact on urban housing as well.

In the 1960s and 70s in metropolitan areas many people and businesses found that new suburban quarters could be more cost effective and of higher quality than what was available in cities. Others were even willing to pay a premium for new buildings and facilities in suburban settings. Within cities it was also common for the cost of renovating an older building, to comply with contemporary standards, to exceed the amount for which the building could be rented or resold. As a result, urban buildings were often abandoned, burned down as part of insurance scams, demolished, or sold to the government for highway, public housing, or urban redevelopment projects. While government use of eminent domain played a prominent role in mid-century federally-funded construction programs, many people willingly, and even enthusiastically, sold their properties to the government. Others sold their aging urban houses at a discount to realtors, some of whom fixed up the houses using home improvement loans and then resold them or rented them out.

BARRIERS TO HOUSING ATTAINMENT

The history of discrimination in housing is complicated. First of all, there are many forms of discrimination. Some discrimination, like behavioral discrimination, is rational and legal, while some of it, like racial discrimination, is irrational and illegal. Significant effort has been put into rooting out racial discrimination through the legal system. Prior to 1913, local governments could adopt race-based zoning. Prior to 1948, states could use their police power to enforce private deed restrictions that prohibited people of designated ethnic backgrounds from purchasing or living in a house with such a deed restriction filed on the land records. Prior to 1968, it was legal for individuals in the private market to refuse to sell or rent a house to someone solely based on their racial identity. Racial discrimination in housing, despite being illegal today, persists and is often very difficult to identify, prove, and prosecute.

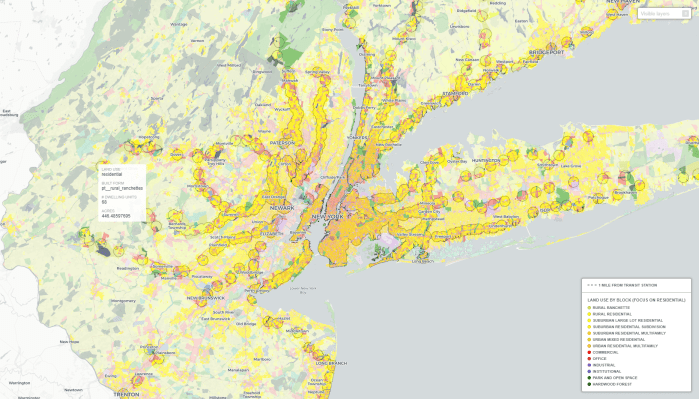

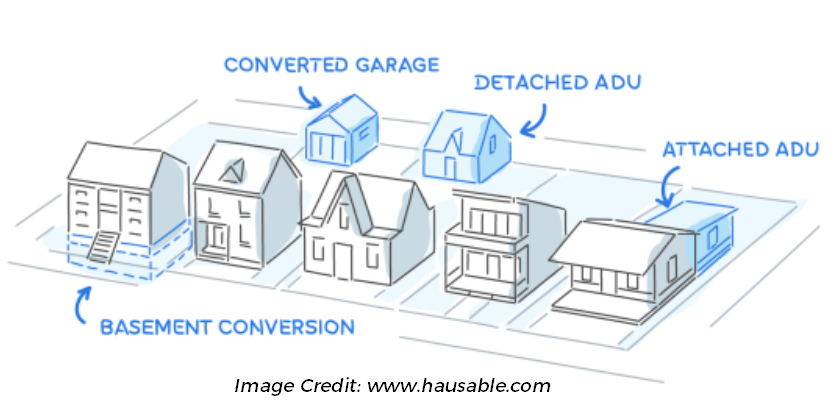

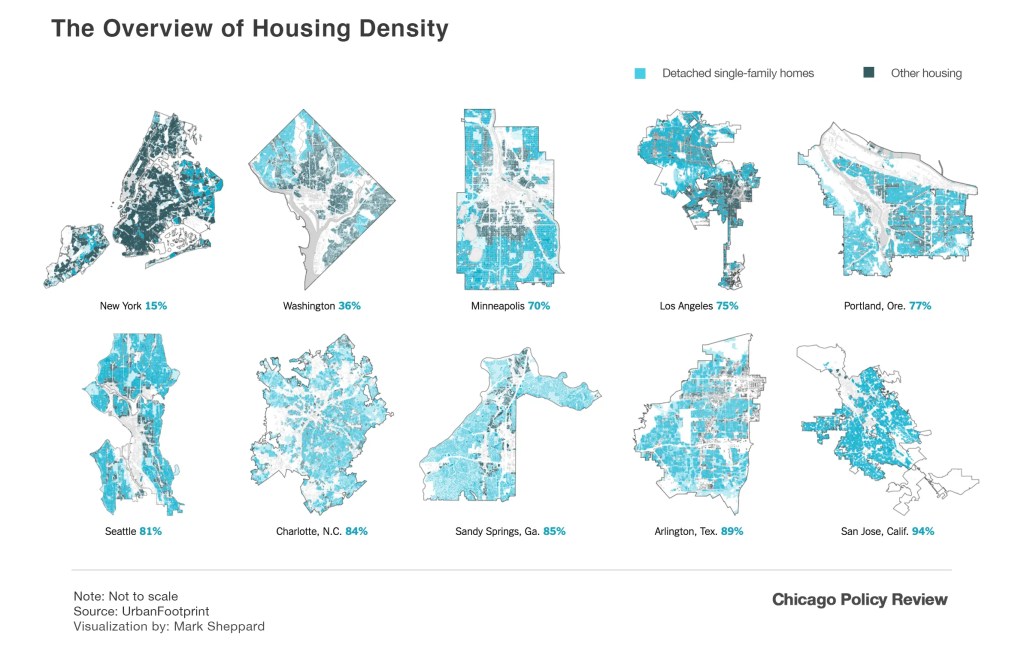

Many housing advocates believe that a next step in rooting out racial discrimination in housing is eliminating exclusionary and highly-restrictive zoning. One popular idea in recent years has been a call to allow multifamily housing in single-family zones. The authors of Escaping the Housing Trap are supportive of efforts to allow middle housing development in single-family neighborhoods. Importantly, they also have their eyes on a larger barrier.

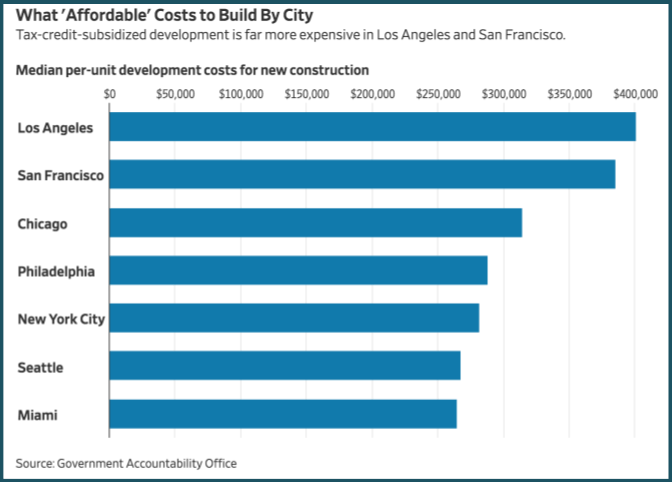

Our dependence on highly-planned professional real estate developments, whether they are privately-financed or publicly-subsidized, is a major challenge to meeting market demand and addressing housing insecurity. Unleashing a pack of semi-amateur developers of small and middle scale housing into their local communities may be able to help address our dependence on professional developers, but there is a bigger issue that, to my knowledge, the Strong Towns movement has not yet articulated.

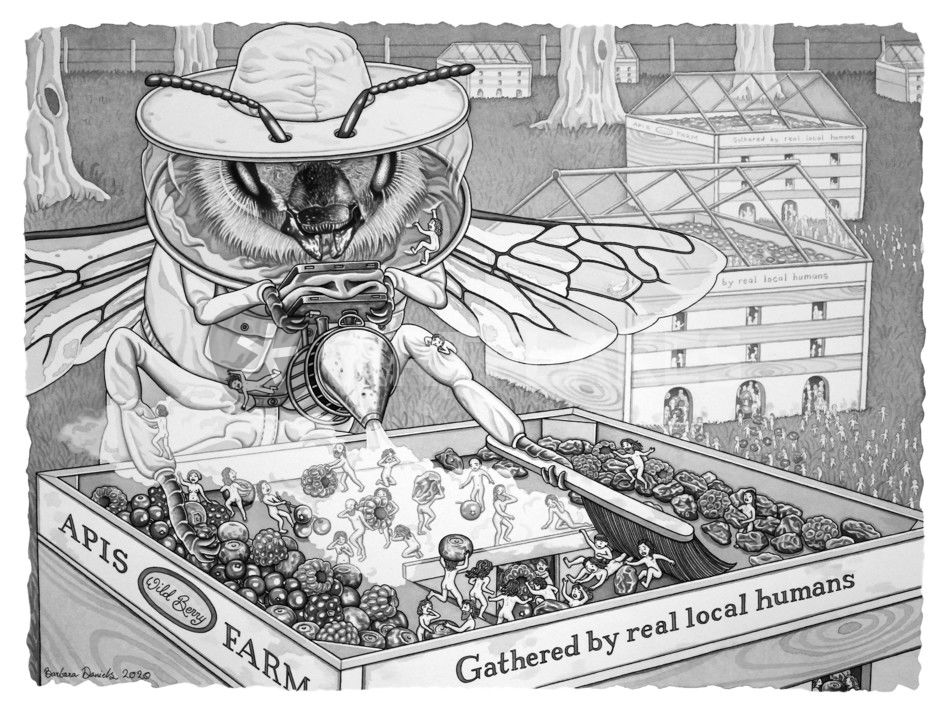

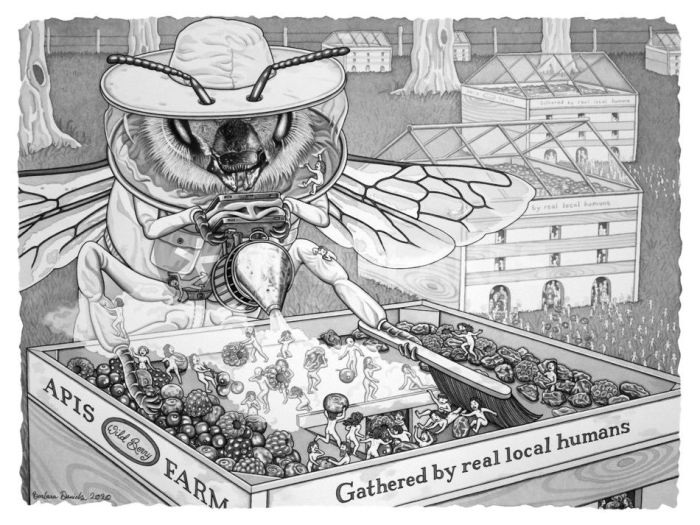

ESCAPING THE HUMANKEEPING TRAP

Humankeeping, or the practice of providing housing for others’ occupancy, is necessary for a healthy private housing market and for meeting the needs of those unable to attain housing through conventional methods. Humankeeping (whether privately- or publicly-financed, or instantly- or incrementally-developed) is only a part of the puzzle. Alternatives to humankeeping are needed as well. Public sector action by governments can help encourage an optimal balance between humankeeping and its alternatives as part of a comprehensive effort to meet everyone’s housing demands.

The Strong Towns movement’s theoretical framework currently lacks this aspect of the housing conversation. While smaller-scale developers, missing middle housing providers, and local landlords can certainly expand housing options beyond what the developers of highly planned communities and government subsidies can provide, these incremental developers also cannot scale to fully meet demand. Humankeeping alone cannot solve the issue, whether it is practiced by large-scale professional humankeepers or by cadres of smaller-scale humankeepers. Luckily, there exists a third way of building housing and a conceptual framework that incorporates and expands upon the Strong Towns approach. To learn about this perspective, take a look around this website and keep an eye out for future content.